On September 12, 2019, I’m looking forward to sharing a new blog entry at TCEA’s TechNotes blog entitled, Strategies That Work. I’m excited about that blog entry because in it, I share a multimedia text set (MMTS) on the top strategies as well as revisit the Strategies That Work app for your mobile device (created with Glidesapps.com) shown right.

Here’s the lead from that upcoming blog entry:

“We have a wide array of instructional strategies implemented,” Terri said. “We use depth and complexity to improve student understanding.” Like this fourth grade educator, many educators rely on classroom instructional strategies. These strategies differ in effectiveness, as John Hattie’s meta-analysis shows. Often, these most effective strategies are unknown to classroom teachers. This blog entry suggests one way to introduce them to effective strategies.

I have to cite TCEA’s TechNotes blog entries on John Hattie since I was completely IGNORANT and oblivious to the imports of the research on instructional technology (a.k.a. edtech). While presenting this summer at various conferences, I observed that many present (I asked them to indicate with hands raised) also had no clue as to John Hattie’s work.

‘What is most important is that teaching is visible to the student, and that the learning is visible to the teacher. The more the student becomes the teacher and the more the teacher becomes the learner, then the more successful are the outcomes’ -John Hattie

Although I won’t give away the main thrust of this blog entry, I have to share some additional “aha” moments I experienced while reading Hattie’s Visible Learning books. Before I jump into analyzing the chart cited, let’s do a quick review of Hattie’s main message.

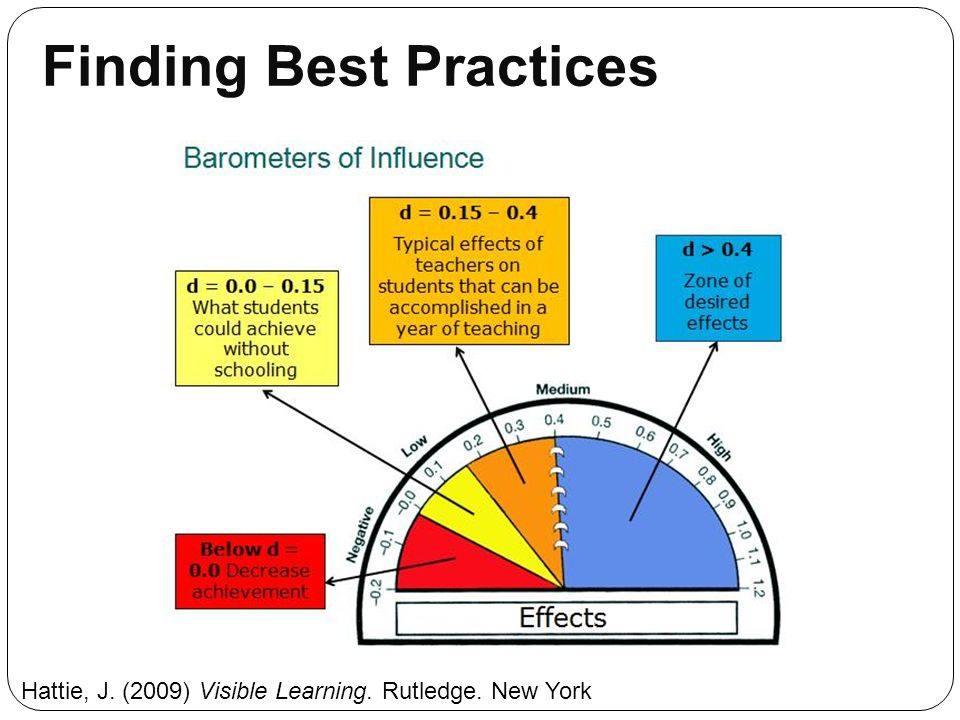

Reviewing Hattie’s Barometer of Influence

In Research-Based Strategies Part 1, Lori Gracey explains Hattie’s barometer of influence in this way:

If a study says that something has an effect size below 0.0 (the red zone), then it has an actual negative impact on learning. Moving between schools, for example, has an effect size of -0.34 and a lack of sleep has a negative effect size of -0.05. (A word of caution: if a vendor is trying to sell you a product with a negative effect size, don’t buy it!).

If a study says that something has an effect size between 0.0 and 0.15 (the yellow zone above), then it has the same effect on learning as you would expect to happen over one year for students who did not attend school but simply matured. It’s not a negative effect; it just doesn’t make any difference. Single-sex schools (0.08) and school choice programs (0.12) are two examples.

If a study says that something has an effect size between 0.15 and 0.4 (the orange zone), then it has the same effect on learning that you would get from students attending school for one year. Examples include summer school (0.23), preschool programs (0.28), and ability grouping for gifted students (0.30). These aren’t bad; they just don’t provide as much “bang for the buck” as might be hoped.

What we want to see is an effect size of 0.4 or greater (the blue zone), meaning that the phenomenon causes a significant difference in learning. Anything above that magic 0.4 number is golden.

Want to read a less favorable, research-based perspective? Check out this article, Has John Hattie Really Found the Holy Grail on Teaching? It offers a less rosy, if no more comforting, perspective.

Does EdTech Work?

This is the question that I’m grappling with. Often, we combine edtech with exciting strategies such as PBL, inquiry-based learning, constructivist approaches, etc. These provide the “research-based” approach used to justify edtech in the classroom. However, what happens when those strategies are shown as bankrupt?

“Put simply, ensuring that every child attains a baseline level of proficiency in reading and mathematics does more to create equal opportunities in a digital world than can be achieved by expanding or subsidizing access to high-tech devices and services.” as cited here

Two powerful points that Hattie makes that struck me:

“We have no right to teach in a way that leads to students gaining less than d=.40 within a year.”

That’s a powerful statement. What it means to me is that I shouldn’t be wasting time encouraging teachers to adopt instructional strategies that do not accelerate student growth.

The second powerful point is this one. It is quite insightful and immediately obviously true:

“One of the more difficult tasks is to convince teachers to change their methods of teaching. So many adopt one method and vary it throughout their career.”

When I reflect on my own work, I can definitely see what strategy I adopted early in my work. That strategy is problem-based learning (PBL). Look through my work, and you will find that PBL is everywhere. Now, my use of PBL doesn’t make me a bad person. But when I consider PBL’s effect size, I have to ask, “What strategy SHOULD have I been spending more time advocating for?”

In problem-based learning scenarios, students often act in groups and decide what they need to learn to resolve a particular problem or question, while teachers act as facilitators. It usually involves real-world problems to promote student learning of concepts and principles as opposed to direct presentation of facts and concepts. The aim is also to promote critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and communication skills.

This is based on evidence from Visible Learning’s Meta X:

Evidence

- Number of meta-analyses: 21

- Number of studies: 794

- Number of students: 96,275

- Number of effects: 1,439

- Effect size: 0.35

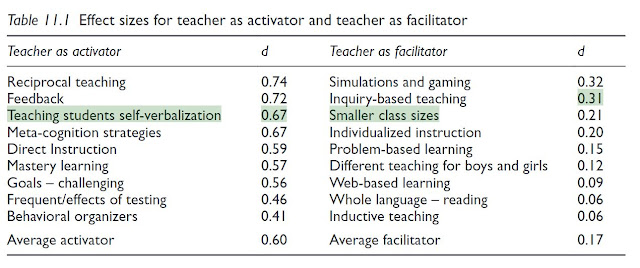

Ironically, I was introduced to a high-yield (.74) instructional strategy EVEN BEFORE I learned about PBL. That strategy was Reciprocal Teaching, which I’ve written about a few times as well. When you compare the effect size of PBL (.35) to Reciprocal Teaching (.74), the difference is considerable. However, PBL only falls into “typical effects in one year of teaching” area of the Barometer of Influence.

We can do better, right?

Teacher as Activator vs Teacher as Facilitator

Take a quick look at the chart below (Table 11.1). On the left side, you see the “teacher as activator.” On the right, “teacher as facilitator.” When I look at the latter, I’m struck by the number of activities that I had the opportunity to facilitate in my classroom. Worse, these are activities I facilitated in my various roles as director of instructional technology and district technology director.

“Constructivism too often is seen in terms of student-centred inquiry learning,problem-based learning, and task-based learning, and common jargon wordsinclude “authentic”, “discovery”, and “intrinsically motivated learning.”

The role of the constructivist teacher is claimed to be more of a facilitation to provide opportunities for individual students to acquire knowledge and construct meaning through their own activities, and through discussion, reflection and the sharing of ideas with other learners with minimal corrective intervention….

These kinds of statements are almost directly opposite to the successful recipe for teaching and learning…” (Source: John Hattie, Visible Learning as cited).

Research (see my bibliography below) shows that constructivist learning is congruent with how the brain learns. There is plenty of research to prove, that constructivist education is the best way for learners to learn. Constructivist education is when . . . learners actively construct meaning by building on background knowledge, experience and reflect on those experiences.

“We have a whole rhetoric about discovery learning, constructivism, and learning styles that has got zero evidence for them anywhere.”

Discover more from Another Think Coming

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.