Only a few days ago, Tim Holt was taking me to task for pushing pseudo-science. The more I read about science stuff, like the incredibly interesting Johnjoe McFadden book, Life is Simple: How Occam’s Razor Set Science Free and Shapes the Universe, I find myself critical of everything. Not “critical” in the way that I get grumpy like a curmudgeon, whining about how lousy things are relative to something else.

It’s easy to think we’ve mastered critical thinking in a modern age. But it’s a process each person must learn and practice daily. In spite of past efforts, it remains important that educators show their students how to think critically.

In my blog entry, I quote Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 thinking. Daniel Kahneman referred to these as fast or slow, respectively:

“System 1 operates automatically and quickly. It works with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control”

“System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it. It includes complex computations” (as cited in source)

One of the reasons blogging is so wonderful? When writing, you experience slow thinking:

We follow a checklist or list of steps that involve adding items to our memory. New information, mixed with long-term memory, finds a place in our minds. We leverage what we know to explain what we don’t fully comprehend. The more we experience, the more sense it makes.

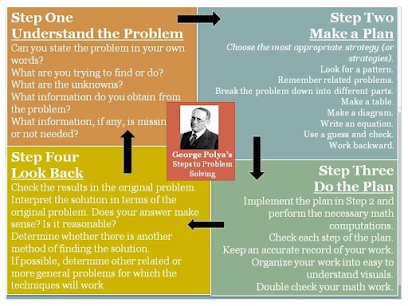

That’s why I am trying to internalize Polya’s approach, as expressed below, although there are other versions that may be appropriate:

I try to capture this in my Evidence-Based Strategies Google Sites, a collection of websites that articulates my understanding of how everything fits together. That is, a magic formula for approaching teaching and learning.

Pseudoscience is not bad science or fake science. Erroneous scientific results are not necessarily pseudoscientific. Bad science results in incorrect or unsound conclusions, usually drawn from valid premises, while pseudoscience presents sound conclusions based on invalid premises. The latter is intentionally deceptive in nature. (source)

The Critique

“To believe Hattie is to have a blind spot in one’s critical thinking when assessing scientific rigour. To promote his work is to unfortunately fall into the promotion of pseudoscience.” Pierre-Jérôme Bergeron as cited in The Cult of Hattie

Evidence-based education (EBE) is the principle that education practices should be based on the best available scientific evidence, rather than tradition, personal judgement, or other influences. Source: Wikipedia.

Just because an explanation springs easily to mind and does require much thinking about doesn’t mean it’s either simple or sensible. We run into this kind of intuitive thinking in education all the time. Teachers are often guilty of assuming an intervention is effective because they see students getting on with stuff and apparently enjoying it.

Does this mean their intervention will be effective in the long term? It’s easy to say yes of course it will, but how do we know?

After all, students producing work and being engaged are poor proxies for learning. Source: David Didau

Hattie’s Pseudoscience

“Educational research will never tell teachers what to do; their classrooms are too complex for this ever to be possible. ” –Dylan Wiliam, as cited

Discover more from Another Think Coming

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.