I can’t tell you how many times I’ve listened to this podcast, Thinking Clearly, featuring Melanie Trecek-King. Here’s the description for the podcast, which is well-worth a listen by educators:

Our guest, Melanie Trecek-King, Associate Professor of Biology at Massasoit Community College, became dissatisfied with students mindlessly memorizing facts about biology, so she designed a general-education science course that puts less emphasis on facts and more on science and information literacy and critical thinking. Her commitment to these topics also prompted her to create the wonderful teaching and resource-filled website, which can be found on-line at: Thinking Is Power.

There’s so much to unpack in this podcast, I’m not going to try…it’s worth exploring it in small bites.

Bayesian Thinking?

Every time I listen to it, I hear something new. One concept that Bob, one of the hosts (Bob and Julia are the hosts), mentions in passing is “Bayesian thinking.”

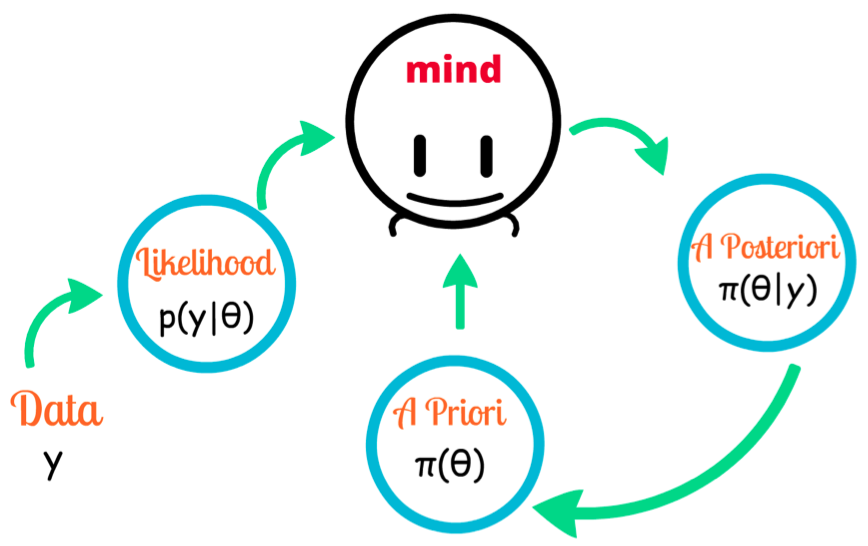

Bayesian thinking? What the heck is that? I immediately googled it. What could that mean? Of course, I ran into this amazing diagram that I had to decipher a bit:

If you click on the source, you end up at a website that shows a coin example using Bayes Theorem:

Whew, that’s intense! I wonder if this is one of the reasons that “critical thinking” gets pushed to the side. My brain is balking at that coin example. But the first diagram seems a bit more understandable.

Deciphering the Diagram

Some of these terms, I haven’t seen again since that summer college class on Philosophy 101. I remembered being mind-boggled at the time, and it was easy to cram it then forget it. Now, I wish I had done the whole Cornell Notes thing, kept a long-time notebook, applied it to every aspect of my life. But, hehe, no, that didn’t happen.

So, what do these terms mean?

- Mind: This is you or me.

- A Posteriori: This is our prior knowledge or experience. “Apples are sweet” is my experience (well, except when they aren’t sweet, but you get the idea).

- A Priori: This is something you know without a statement of fact and is not a result of direct experience. An example of a priori would be a logical statement, such as, “Every apple is a fruit.” It isn’t specific to a case.

- Data: This is new information that we always have coming in.

- Likelihood: This is the intensity of something happening based on data, which is always changing or being updated.

Ok, I KNOW I didn’t get that right. I’m not sure I understand “Data” and “Likelihood” and the relationship between them. This more in-depth explanation may help.

|

| Image Source: Bayesian Thinking Real Life Examples |

I am totally confused about this, but hey, I need to dedicate more time to learn and reflect. Not to be stopped…

Principles of Bayesian Thinking

Ajay, who came up with the diagrams above, explains it in a series of principles of Bayesian thinking. You can read his example in his article. For fun, and trying to make it stick, I’m going to make up an example. Here’s hoping this blog entry doesn’t take six hours (well, it won’t, because I’m going to bed in an hour, no matter how long this takes):

Example: One afternoon, I head over to the grocery store. As I arrive, I notice that there is a huge crowd of people at the front registers.

The question to infer is: Why are there long lines at the front registers? There might be several possible answers to the question.

Here are a few possible scenarios as to why:

- The front cash registers are broken. The digital system has broken down or there was a power outage, and nothing is working.

- There are only a few cash registers open. This results in some long lines, as people are stuck.

- All cash registers are open but people are anticipating a natural disaster (e.g. bad storm, hurricane). People are anticipating they will need supplies.

- A guy with an automatic rifle is robbing the store, and he’s got everybody huddled together for crowd control.

Ok, here’s my application (probably wrong) of the principles of Bayesian thinking:

- Use prior knowledge. Based on other factors, such as lack of police cars out front, joking and relaxed attitude of people in line, chances are Scenario #4 is not accurate. I haven’t walked into a potential active crime scenario.

-

Use your observations wisely. In this one, I want to “choose answers that explain the observations the most.” When I look, I see that all the cash registers, that are open, appear to be working. As such, I disregard Scenario #1…cash registers appear to be working fine.

- Don’t make extra assumptions. People might be there in response to a natural disaster. It’s possible I didn’t hear about one on the news, but this would have to be a massive panic. I’m making too many assumptions about too many people. This eliminates Scenario #3.

With these points in mind, the solution is most likely that there are only a few cash registers open. When I arrive, I discover the store is short-staffed today, and not all lanes are open. Even working at top speed, long lines have sprung up.

I’m not sure if that example works perfectly but you can always go read Ajay’s original and see.

Wrap-Up

Well, that was a rabbit hole. I see the wisdom in Melanie’s response to the question of whether she teaches Bayesian thinking to her students when addressing critical thinking. You’ll have to listen to hear her response.

Discover more from Another Think Coming

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.