Preparing for a workshop the first weekend in December, I asked myself, “Wouldn’t it be cool to have an online assessment for Gen AI fluency but for a specific group?” I’d seen a presentation from Section, where they shared Zapier’s AI Fluency assessment. As you might guess, I wasn’t the only one inspired to modify the AI fluency assessment (given that it’s so simple, not valid or reliable, more of a gut check) Zapier had crafted.

…elected officials and Silicon Valley executives are trying to open classrooms to a technology that could set students back even further than mobile phones have: artificial intelligence. (Source: AI Can’t Replace Classroom Educators)

What surprised me, though, was how easy it was to use ChatGPT to guide me through (er, tell me what to do) modifying an assessment, converting it into a GitHub Page, then saving the data from that assessment to a Google Sheet. Where has ChatGPT been all my life? Oh, that’s right.

Wait, What About Eroding Your Coding Skills?

I have followed with interest the MIT Project Iceberg report. And, I’ve seen The Atlantic’s article:

After three years of doing essentially nothing to address the rise of generative AI, colleges are now scrambling to do too much…a new initiative promising to “embed AI education into the core of every undergraduate curriculum, equipping students with the ability to not only use AI tools, but to understand, question and innovate with them—no matter their major.” …such policies represent a dangerously hasty and uninformed response to the technology. Based on the available evidence, the skills that future graduates will most need in the AI era—creative thinking, the capacity to learn new things, flexible modes of analysis—are precisely those that are likely to be eroded by inserting AI into the educational process. (Source: Michael Clune, Colleges Are Preparing to Self-Lobotomize, 11/29/25, The Atlantic)

And, I agree completely with this argument. We simply should throw out all technologies that don’t enhance creative thinking, critical thinking, analysis, even when the casualty is learning how to better use technology in the future or facing the threat that children will use technology with poor role models (or no models at all to guide them).

Really, how much are classroom teachers required to do today? Let’s try long-term information retention, evidence-based instructional strategies, and stop shoving every new technology into the classroom so that Big Tech can make a buck.

Now that you know what I really think, let’s get back to my problem of publishing an assessment that collects data from the web. Since, unlike K-16 students, I’m not going to bother learning how to code. Vibe-coding or whatever the latest moniker is to describe whatever AI-powered coding (you know, where it does all the work and I use natural language to modify it) is, works.

Gen AI Does NOT Work

Oh, wait, you’re saying, “Gen AI is hallucinating, not working, and you’re just wasting your time. Worse, you aren’t going to be able to revisit the code in a year and fix it.” Well, I hate to break it to you, but I don’t care. This is a quick coding project and if I have to fix it, I’ll just re-do it then using an even better hallucinogen, er, Gen AI.

What Was Generated

Here’s the process I followed to generate a GitHub Page, which I had NEVER done in my life, and couldn’t have done (to be blunt) or been bothered to do until Gen AI coached me through the steps. I was freakin’ amazed to get a working result, then have it make it possible to put the results into a Google Sheet.

You can see (and try out) what was made online. Here’s a screenshot of a more developed version, which I’ll be using later down the road:

How Gen AI Did This

The process is outlined below…it’s a Gen AI account of the steps followed. Enjoy!

From Assessment to GitHub Page: A Simple Workflow That Works

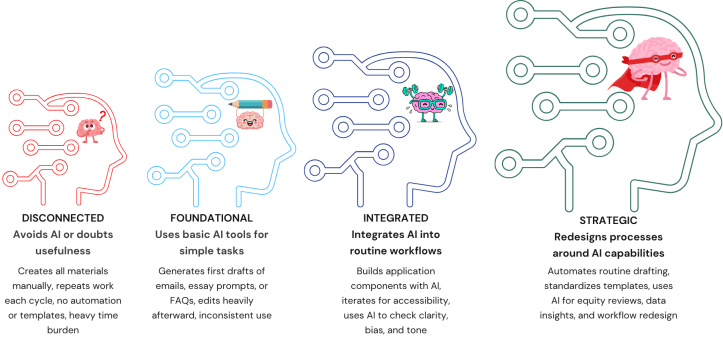

I started with a straightforward goal: take an AI Capability Ladder self-assessment—something I’d been refining—and make it publicly accessible in a clean, shareable format. The problem was that the assessment lived as a local file. It wasn’t easily viewable, linkable, or usable by others.

So I pushed it through a short workflow: assessment → HTML file → GitHub repository → GitHub Pages website.

Here’s the path.

Step 1: Start With the Assessment

I already had the content prepared: text, an image, and an index.htm file. Good enough to render in any browser. But it wasn’t online yet, and I didn’t want to bury it in cloud storage links. I wanted a simple public URL.

That meant GitHub Pages (since I didn’t have anything else, but I recalled I’d set up a GitHub account for a blog backup).

Step 2: Create a New Repository

Since my main repository already had other published content, I didn’t want to overwrite or disrupt it. The cleanest move was to create a new GitHub repo dedicated to the assessment.

One repo → one clearly defined microsite.

So I created a new repo named something like:

aicapabilityladder

I uploaded the assessment files (HTML + image + license). ChatGPT generated the HTML and I made the image in Canva.

Step 3: Fix the File Structure

GitHub Pages needs a homepage named exactly:

index.html

I renamed my existing index.htm file. This step matters—without it, GitHub Pages won’t display your site’s front page. Since I hadn’t used GitHub much, renaming the page and updating the content of the HTML was a learning experience. No doubt, folks who use GitHub all the time know how to do this already.

Step 4: Enable GitHub Pages

Inside the repo:

Settings → Pages → Build and deployment

- Source: Deploy from a branch

- Branch:

main - Folder:

/ (root)

Save.

After a short build, GitHub generated a live URL such as:

https://<username>.github.io/aicapabilityladder/

Now the assessment was a standalone public site, hosted for free, automatically updated every time I commit changes.

Step 5: Confirm, Share, and Iterate

After the site went live, I tested it in a browser. Everything loaded as expected: layout, image, text. No complexity. No frameworks. Just clean HTML being served directly.

Now I can:

- update the HTML anytime

- add pages

- drop in diagrams, images, or scripts

- share a simple link in presentations or documentation

The assessment now behaves like a small, portable website.

Why This Workflow Works

- No dependency on platforms

GitHub Pages is stable, public, free, and portable. - All files version-controlled

Every change is safe and reversible. - Zero overhead

No CMS. No hosting fees. No setup beyond renaming a file and clicking a switch. - Expandable

Today, it’s one assessment. Tomorrow, it could be a whole library of AI tools.

Final Result

A local assessment became a public resource with a stable URL, version control, and a permanent home. The entire process took only a few steps:

- Create new repo

- Upload files

- Rename homepage to

index.html - Enable GitHub Pages

- Share the live link

Of course, this was only the first iteration.

A GitHub Page cannot directly write to a Google Sheet, because GitHub Pages is static hosting (no server, no backend).

But you can connect it using a lightweight method:

Use a Google Apps Script web app as the backend

Your GitHub Page → sends form data → Google Apps Script endpoint → writes to Google Sheet.

Below are the steps in plain, direct sequence.

1. Prepare Your Google Sheet

- Create a new Google Sheet.

- Add column headers (e.g., Timestamp, Name, Score, etc.).

- Open Extensions → Apps Script.

2. Add this Apps Script

Replace everything in the script editor with:

function doPost(e) {

var ss = SpreadsheetApp.getActiveSpreadsheet();

var sheet = ss.getSheetByName("Sheet1"); // change if needed

var data = JSON.parse(e.postData.contents);

sheet.appendRow([

new Date(),

data.name,

data.email,

data.responses

]);

return ContentService.createTextOutput(

JSON.stringify({status: "success"})

).setMimeType(ContentService.MimeType.JSON);

}

Adjust the fields to match your GitHub Page form.

Click Save.

3. Deploy it as a Web App

- Apps Script → Deploy (top right).

- Select New deployment.

- Type: Web app

- Execute as: Me

- Who has access: Anyone

- Deploy.

- Copy the generated Web App URL — this is your backend endpoint.

Example:

https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbx.../exec

4. Add a Form to Your GitHub Page HTML

In index.html (or wherever your form is), include something like:

<form id="assessmentForm">

<input type="text" name="name" placeholder="Your name">

<input type="email" name="email" placeholder="Your email">

<textarea name="responses" placeholder="Your assessment responses"></textarea>

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>

<div id="status"></div>

5. Add JavaScript That Sends the Data to Google Apps Script

Put this at the bottom of your HTML or in a separate .js file:

<script>

document.getElementById("assessmentForm").addEventListener("submit", function(e) {

e.preventDefault();

const url = "YOUR_WEB_APP_URL_HERE";

const data = {

name: this.name.value,

email: this.email.value,

responses: this.responses.value

};

fetch(url, {

method: "POST",

mode: "no-cors",

contentType: "application/json",

body: JSON.stringify(data)

});

document.getElementById("status").textContent = "Submitted!";

});

</script>

Replace:

YOUR_WEB_APP_URL_HERE

with the URL from Step 3.

6. Push the updated HTML/JS to your GitHub Page

Commit → push → wait 1 minute → your site now sends its responses into the Google Sheet.

7. Test

Submit the form from your GitHub Page → check the Google Sheet → new row should appear.

Summary Flow

GitHub Page (HTML Form)

↓ POST

Google Apps Script Web App

↓ appendRow

Google Sheet (Stores responses)

And, it worked. I’m sure there are other exciting options and ways to do this. But as a person who never learned to code (even though I tried again and again), I’m happy to say, this result is “good enough.” I’ll have to go through it a few thousand more times to be comfortable with it, but when someone says, “Gen AI won’t work,” I’ll say, “You know, it works well enough.”

Can you imagine what Gen AI can do in the hands of someone who knows how to code? Wow.

Of course, to get that expert coder, familiar with failure, adapting and overcoming, we should probably keep Gen AI out of K-16 classrooms.

A Few Parting Thoughts

I love this piece by Carl Hendrick:

The lesson here is not that AI has discovered a new kind of learning, but that it has finally begun to exploit the one we already understand.

But let’s be clear. Again, the history of Edtech is a story of failure, very expensive failure. This is not merely a chronicle of wasted resources, though the financial cost has been considerable. More troubling is the opportunity cost: the reforms not pursued, the teacher training not funded, the evidence-based interventions not scaled because capital and attention were directed toward shiny technological solutions.As Larry Cuban documented in his work on educational technology, we have repeatedly mistaken the novelty of the medium for the substance of the pedagogy.

The reasons for these failures are instructive.Many EdTech interventions have been solutions in search of problems, designed by technologists with limited understanding of how learning actually occurs. They have prioritised engagement over mastery, confusing students’ enjoyment of a platform with their acquisition of knowledge. They have ignored decades of cognitive science research in favour of intuitive but ineffective approaches. They have failed to account for implementation challenges, teacher training requirements, and the messy realities of classroom practice.

…the answer is that teaching and learning are not the same thing, and we’ve spent too long pretending they are. Learning, the actual cognitive processes by which understanding is built, may indeed follow lawful patterns that can be modelled, optimised, and delivered algorithmically.

The science of learning suggests this is largely true: spacing effects, retrieval practice, cognitive load principles, worked examples; these are mechanisms, and mechanisms can be mechanised. But teaching, in its fullest sense, is about more than optimising cognitive mechanisms. It is about what we value, who we hope our students become, what kind of intellectual culture we create.

Source: https://carlhendrick.substack.com/p/the-algorithmic-turn-the-emerging

Discover more from Another Think Coming

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.